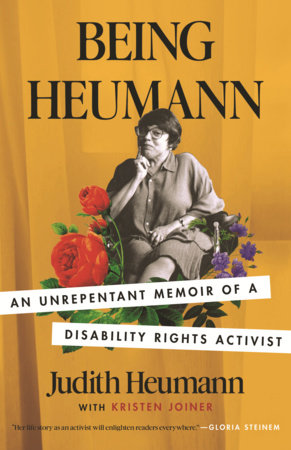

Join DiversAbility at Yale and the Working Women’s Network for a discussion with Judith Heumann about her memoir: Being Heumann: An Unrepentant Memoir of a Disability Rights Activist. A story of fighting to belong in a world that wasn’t built for all of us and of one woman’s activism—from the streets of Brooklyn and San Francisco to inside the halls of Washington—Being Heumann recounts Judy Heumann’s lifelong battle to achieve respect, acceptance, and inclusion in society.

Through Being Heumann, one of the most influential disability rights activists in U.S. History tells her personal story of fighting for the right to receive an education, have a job, and just be human. As part of the all-virtual 2021 Virginia Festival of the Book, this event is FREE to attend and open to the public. Advocate and author Judith Heumann (Being Heumann: An Unrepentant Memoir of a Disability Rights Activist) discusses her book and her life's work. Through Being Heumann, one of the most influential disability rights activists in U.S. History tells her personal story of fighting for the right to receive an education, have a job, and just be human. Heumann has had a distinguished career, which includes stints as a disability rights advisor at the World Bank and the State Department, working for presidents Obama and Bill Clinton.

Please send questions related to the book that you would like Ms. Heumann to discuss to: Melanie Norton (Melanie.Norton@yale.edu) by March 19, 2021. Register by Friday, March 5th for your chance to win a free copy of the book!

Live auto-captions will be provided for this event. If you need an additional disability-related accommodation, please contact: The Office of Institutional Equity and Access (OIEA), at equity@yale.edu. Requests should be made by March 15, 2021.

The prologue to Being Heumann: An Unrepentant Memoir of a Disability Rights Activist by Judith Heumann with Kristen Joiner starts with the words, “I never wished I didn’t have a disability.”

It’s a powerful way to begin a memoir, one that I can appreciate probably has a different impact on nondisabled readers than it did on me. This might be the first time nondisabled readers have come across that sentiment, as Heumann points out in Chapter 12, aptly titled “Our Story.” Heumann connects popular contemporary media portrayals of disability, such as Me Before You and Million Dollar Baby, to her own story. “What if someone’s story began with the words: ‘I never wished I didn’t have a disability,’” she writes, bringing the book full circle back to its opening line.

Heumann’s memoir, which is in equal parts a history lesson on disability rights activism in the United States and an intimate look at her life from childhood to present, centers on ideas of disability rights, community, access and equity, independence, autonomy, and disability pride.

From the very beginning chapters, I was hooked. Unlike Heumann, I was born with my disabilities (primarily autism and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) and I am not a wheelchair user, but many of her childhood experiences mirrored mine. “The first time I’d ever met another disabled kid was when I went for the evaluation,” she writes in an early chapter about the access barriers she faced while trying to get a primary school education. The writing is concise and evocative and she draws the reader into every scene. I felt like I was right there with young Judy, rolling to her friend Arlene’s home, yelling for her to come out and play because there was no accessible entrance.

It’s a challenge to write a book that centers so strongly on disability rights without pandering to a nondisabled audience, but Heumann clearly trusts that all her readers will get it. Heumann has faced many people throughout the years who don’t know they’re being ableist—telling her that she can’t attend public school because her wheelchair is a fire hazard or not granting her a teaching license because her wheelchair is unsafe for young kids. But she knows that the best way to win people over, including her readers, is to be honest with them and give them the opportunity to empathize with her instead of distancing themselves from the disabled experience.

Heumann’s writing does not hold back. She is unafraid to share the most difficult moments with us, such as when other children insisted that she must be sick because she used a wheelchair or when she felt like a burden simply for asking for equal access. “I recognize now that exclusion, especially at the level and frequency at which I experienced it, is traumatic,” she writes, and she continues to show us what this looks and feels like throughout the memoir. It’s traumatic to be asked to leave an airplane because you have a disability, or to be unable to attend the same social activities as your fellow college students.

Heumann contrasts this with the pure joy and collective access of being part of the disability community. She experienced this at a camp for kids with disabilities and in her special education classroom, and she experienced it as an adult disability activist in her work with organizations like Disabled In Action, the Center for Independent Living, and World Institute on Disability. “We treasured the ability to create our own space, where our communication needs, and their slower pacing, were respected,” she writes about the long meetings she and other protestors had while they were fighting for Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 that prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability. Those meetings, and their work, were designed around collective access: waiting patiently for everyone to speak, making sure people had access to their medications, using American Sign Language and translators.

Collective access is a major theme in Heumann’s memoir, both in her personal life and in her activism. “Institutions don’t like change because change takes time and can entail costs,” she writes, and she also argues that people need to assume it’s possible to figure out accessibility and problem-solve and take action. Heumann comes across many excuses in her activist work for why existing institutions—such as schools, public transportation, and the government—can’t or won’t change. She and her fellow activists don’t take no for an answer. Throughout the book, Heumann takes matters into her own hands; she personally calls event organizers to challenge them when they question why a young disabled person should be invited to attend.

Heumann is truthful about her place in the world as a Jewish disabled woman, and she recounts the erasure she experienced within the larger women’s rights movement, which ignored disability at the time. “What a pervasive influence silence and avoidance have had on my life,” she writes, in a scene where she is connecting her Jewish identity and the silence surrounding the Holocaust to the silence she encounters as a disabled woman.

She’s also thoughtful and honest about both her position of privilege as a white person with access to education and healthcare and the sexism she encounters as a disabled person. She credits other marginalized groups, particularly Black people and the LGBTQ+ community, for showing up for disabled activists when no one else would. But there were several times in Being Heumann that she used the civil rights movement and the Black experience in America with the disabled experience, which I felt almost conflated the two and ignored the existence of disabled people of color. These connections are meant to show readers how ignored disability rights were at the time when Heumann and her fellow activists were fighting for Section 504 and the ADA, but they sometimes miss the mark. Many white disabled people are quick to suggest that they understand what it’s like to experience racism because we experience ableism, but the two experiences are not the same, and our whiteness will always offer us a level of privilege and visibility that disabled people of color are not afforded in this country.

On the whole, many of the disability rights issues raised in Being Heumann are improving. Heumann recounts how a curb was like the “Great Wall of China” when she was a kid; if her friend lived on the other side of the street, it would have been literally impossible for her to get off the curb without curb cuts. Her memoir details some of the ways that disability rights have been won, and the steps backward we’ve taken as well—the passing of the Affordable Care Act, and legislation created to weaken it. I was surprised by just how much of her memoir, and the access barriers she’s faced, feel universal and timeless. “I did sometimes feel a little awkward about getting schlepped up the stairs backwards to Brownies, or getting carried down the back steps and through the garbage behind the synagogue to get to the elevator for Hebrew class,” she writes in an early chapter about her childhood. In 2020, nearly 30 years after the Americans With Disabilities Act passed, I still encounter public spaces where my friends and I have to carry a friend who uses a wheelchair inside up a set of stairs, and even accessible buildings are known for having their wheelchair-accessible entrance in the back by the dumpster.

At 211 pages, this memoir was concise and action-packed. Every chapter focuses on Heumann’s life, but she’s not a passive participant; she’s quite the opposite.

Being Heumann tells the story of Judith Heumann, but Heumann herself writes throughout the book that the work is not hers alone. She credits her family, in particular her mother, for instilling in her the idea that she could fight for her rights. Her memoir offers a lens to the larger disability rights movement, both in the States and globally, and she writes about the many other activists and friends she’s collaborated with over the years.

Judy Heumann Life Story

Heumann’s memoir is ultimately a story of community, of disabled and nondisabled people coming together for collective access. “This is my story, yes, but I was one in a multitude,” Heumann writes. This is her story and it starts with the fact that she never wished she didn’t have a disability. It’s also all of our story; it’s our history, our movement, and our building block for the future. Heumann leaves the reader in the final chapter with actions we can all take to build a more inclusive world and become involved in modern day activism, and the sentiment that “we have the power. We are changing things.”

Click here to pitch a blog post to Rooted in Rights.

Being Heumann Review